🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

“How are we going to feed nine billion people by 2050?”

That was what everyone was talking about when I entered agricultural college in 2013. It was everywhere—on posters, in lectures, in journal articles. It was my generation’s job to increase production, I was told, since we would be the ones in power in 2050. It was up to us to make sure there was enough food to go around.

Implicit in much of the “feeding the world” discourse were several main assumptions. One was that global food production needed to be increased at a faster rate than population growth to wipe out hunger. Another was that science and technology were the keys to increasing production worldwide—and that organic production or traditional agricultural practices just weren’t productive enough to do the trick. Most importantly, we were told that it was the responsibility of American scientists and farmers to figure out how to feed the world.

As I have looked into the origins of the “feeding the world” rhetoric, it seems that it was influenced by two major ideas. One was the Malthusian concern that population would outstrip food supply, which I discussed in my last Wise Traditions article.1 However classic Malthusianism didn’t try to help feed people, because it was based on the assumption that there could never be enough food to go around. At the same time, a humanitarian goal of eliminating hunger and poverty worldwide was gaining ground. The idea that the world could become a better place if everyone got enough food to eat was promoted by many people, but its most passionate advocate was a Scottish nutritionist named John Boyd Orr.

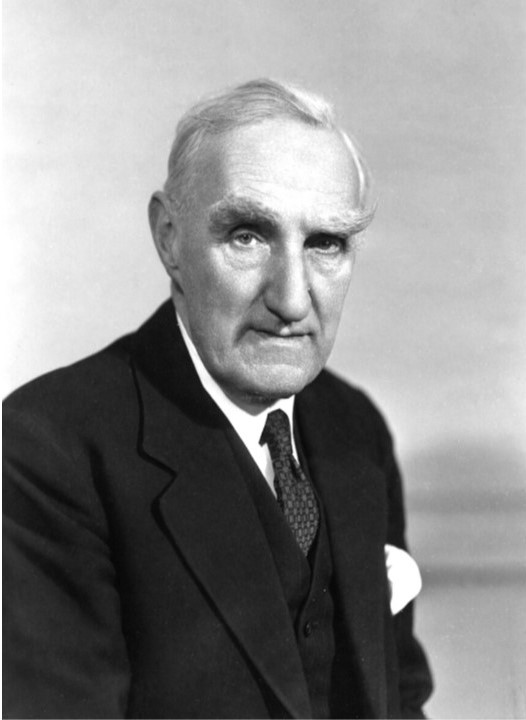

JOHN BOYD ORR

“Sir John Boyd Orr, the craggy Scotsman who heads the Food and Agriculture Organization, is a man you would look at twice in any crowd,” wrote Henry Jarrett in a 1947 article for the magazine The Land. “The gaunt dignity and the banked-up fire in the man remind you somehow of an elemental force of nature, like the wind and tide. He acts like one when his ideas for food and human welfare are at stake.”

Born in Scotland in 1880, Boyd Orr got his first look at hunger and poverty after he graduated from Glasgow University in 1902 and started teaching school in a Glasgow slum. When he showed up on the first day of class, he was shocked to see that his students were clothed in rags and covered with lice. They were unable to concentrate on their lessons because they were weak and malnourished.

“I went home the first night feeling physically sick and very depressed,” he wrote in his 1966 autobiography As I Recall.2 “I had another look at the school the next day, and came to the conclusion that there was nothing I could do to relieve the misery of the poor children, so I sat down and sent in my resignation.”

Although he worked as a doctor for a brief period and served in World War I, Boyd Orr’s real passion was nutrition—one of the most exciting areas of research in the 1920s. Nutritionists had just discovered that vitamins were essential to human health, and that animals or people who didn’t eat enough vitamins would develop “deficiency diseases” like scurvy, beriberi, rickets and night blindness.

One of the leading vitamin researchers, biochemist Elmer McCollum, led the movement for a healthy diet based on the “newer knowledge of nutrition.” The best way to prevent vitamin deficiencies, he argued, was to include vitamin-rich “protective foods” in the diet. These included leafy green and orange-yellow vegetables, whole grains, whole milk and animal organ meats such as liver.

Boyd Orr followed this research on vitamins with much interest, but he suspected that mineral nutrients, also essential to health, were being overlooked in all the emphasis on vitamins. He helped found the Rowett Research Institute in Animal Health in Aberdeen, Scotland, to study the importance of trace mineral elements in animal nutrition. His book, Minerals in Pastures, published in 1929, was one of the first to consider the role minerals played in animal health.3

Always remembering those poor malnourished children in Glasgow, Boyd Orr began investigating the possibility of improving the health of the poor in Scotland with better nutrition. In 1931, he launched a dietary survey, which discovered that a third of Scotland’s population was unable “to purchase sufficient of the more expensive health foods to give them an adequate diet.” The results of this survey, published in 1936 under the title Food, Health, and Income, showed that the diets of the poor were lacking in minerals, vitamins and sometimes even protein and calories.4 “These diets may be sufficient to maintain life and a certain degree of activity, and yet be inadequate for the maintenance of the fullest degree of health which a perfectly adequate diet would make possible,” he concluded.

Boyd Orr believed that the health of these people could be greatly improved if they were only able to get enough milk and other protective foods. And the results of his survey were fresh on his mind when he made the dangerous wartime crossing of the Atlantic to attend a historic conference in the United States—the first-ever United Nations Conference on Food and Agriculture.

FOUNDING OF THE FAO

Held at Hot Springs, Virginia in May and June 1943, the Conference on Food and Agriculture was the first concerted international attempt to address the problem of world hunger. As those at the conference saw it, the world was faced with two major problems. One was the problem of malnutrition among the poorer classes of people, like Boyd Orr had seen in Scotland. The other problem, ironically enough, was that farmers were producing too much food and suffering economically because they could not make a living selling it.

Instead of curtailing production by destroying crops, as the Agricultural Adjustment Administration had done in the early days of the New Deal, the delegates at the Hot Springs conference envisioned a world where increased food production could eliminate malnutrition. They recommended that agricultural production be greatly increased, based on modern scientific knowledge, and that the world economy be expanded “to provide the purchasing power sufficient to maintain an adequate diet for all.”

“These recommendations are revolutionary,” Boyd Orr wrote in his 1943 book Food and the People.5 If they could be implemented, he foresaw a world where “the power of money over the primary necessity of life will be broken,” where everyone could be “strong and vigorous, both physically and mentally,” with “a feeling of assurance and independence.”

At the 1943 conference in Hot Springs, an interim commission was formed to hammer out the details and write a constitution for a new branch of the United Nations—the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The FAO was officially inaugurated at a conference in Quebec in October 1945, just after World War II ended. John Boyd Orr was selected to be the first director-general of the infant organization.

Boyd Orr had grand visions of ending world hunger and poverty through better food distribution and increased production. He believed that the only way to accomplish this was to set up a “World Food Board,” which would provide loans to “food-deficient” countries to “enable them to purchase surplus foods from food-exporting countries and industrial products needed to modernize their agriculture to increase food production.” These loans would not have to be repaid “until hunger and abysmal poverty had been eliminated.” The World Food Board would also be able to buy and hold surplus food during good years for distribution during lean years. Ideally, he hoped that the World Food Board would eventually lead to a world government, “without which there is little hope of permanent world peace.”

To Boyd Orr and many others, there seemed to be only two choices in the atomic age—“one world or none.” “If nations cannot learn to co-operate on a broad humanitarian basis, such as that found in the F.A.O., they will never be able to co-operate on contentious problems like boundary lines, types of democracy, or atomic bombs,” warned the nutritionist L.B. Pett in the January 1946 issue of the Canadian Journal of Public Health.6 But the most important country in Boyd Orr’s plan, the United States, didn’t like the idea of giving up its newfound position as the most powerful nation in the world for purely humanitarian motives. Sure, Americans would help feed the world—but on their terms, not Boyd Orr’s.

Without the support of the United States or Britain, the World Food Board never materialized. The primary function of the FAO became the gathering and distributing of statistics and other educational information, a very valuable service but one which fell short of Boyd Orr’s original dreams. Disillusioned with the greed and selfishness of the United States, Boyd Orr returned to Scotland, symbolically wiping the dust of America off his feet after boarding the ship. To the end of his days, he believed that if his proposal for the World Food Board had been implemented, it would have brought an age of lasting world peace and prosperity.

Boyd Orr’s proposals for the FAO were not completely ignored. Many of the ideas that went into the original proposal for the World Food Board—loans to developing countries, assistance with agricultural development, channeling of surplus commodity crops to hungry nations—actually did come to pass. What differed from Boyd Orr’s plan, however, was that all of these policies took on strategic significance in the Cold War. Food became not a right, as Boyd Orr had envisioned, but a weapon.

FOOD AND NATIONAL SECURITY

Initially, the FAO’s stated motives for feeding the world were strictly humanitarian. The hope was to bring world peace through mutual cooperation, resulting in a better standard of living for everyone. The United States and other wealthy nations should feed the world, the organization’s experts argued, because it was a noble and compassionate thing to do.

As the Cold War began and the United States began to fear the rise of communism, however, the motives for helping feed the world became much more selfish. The United States was free and prosperous, many argued, only because there was plenty of food for everyone. Some, like Frank Pearson and Floyd Harper in their book The World’s Hunger, even claimed that democracy was only possible on a diet rich in milk and meat, like that consumed in the United States.7 They calculated that the world could support only one billion people at the American standard of living.

Overpopulation, hunger and communism were linked in a direct causative sequence, argued Guy Irving Burch and Elmer Pendall in their 1945 book Population Roads to Peace and War.8 Ollie Fink, executive secretary of the conservation organization Friends of the Land, explained this progression in a 1952 speech entitled “Democracy and Human Freedom are Products of Fertile Soil.” Fink argued, “If a nation is to be made up of mentally alert and physically capable people, the first prerequisite is the equivalent of food from 2 or more acres of arable land.” (See my previous article on Malthus for a discussion of where this statistic came from and why it was flawed.)1 With less than two acres per person, he asserted, “hunger and malnutrition occur with their chain of unfavorable events. . . war, pestilence, disease, poverty.”

In Fink’s view, “Freedom has its roots in the soil.” He explained, “As acres become too few and people too many, the government steps in and regulates the distribution of food. We recognize the type of government as socialist—fascist—or communist.” From this perspective, the only way to prevent this from happening was to increase food production per acre—although Fink had doubts that this could be done quickly enough to preserve freedom.

Overpopulation, Fink and others argued, caused hunger, political instability, communist insurrection, danger to American interests and finally, war. In his 1997 book Geopolitics and the Green Revolution: Wheat, Genes, and the Cold War, historian John Perkins calls this sequence of events “population-national security theory.”9 According to this theory, if world hunger wasn’t addressed, developing countries would turn communist just to get enough to eat, possibly leading to a nuclear war and the end of modern civilization. “Food for everyone might not insure peace,” wrote the soil scientist Charles Kellogg in a 1949 article for the Journal of Farm Economics. “But we can be reasonably sure of the opposite: Without sufficient food for the population of the world peace is uncertain, indeed unlikely.”10

By 1948, two schools of thought about feeding the world had emerged. One was that it was already too late to do anything and that famine and war were inevitable. The other believed that it was possible for food production to keep up with population growth—but only through the application of science and technology to agriculture. John Boyd Orr’s dreams of feeding the world fell into this second category.

Some soil conservationists, like Hugh Bennett, believed that soil conservation and working with nature were the keys to increasing agricultural production. Others proposed radical technological solutions like growing algae and yeast for human consumption. The idea that eventually prevailed, however, was that capital-intensive industrial agriculture was the only way to feed the world.

The official American response to the “feeding the world” dilemma was the Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954, commonly known as PL-480. This program had several functions. It helped get rid of surplus American crops without overwhelming the world market and it provided humanitarian aid for malnourished people. But as historian John Perkins has observed, it also served “as a major instrument for feeding the world’s hungry and for limiting communist expansion in the developing world.”

From 1945-1965, the United States played a similar role to the one that Boyd Orr had envisioned for the World Food Board. American food aid under PL-480 and other programs provided a stabilizing influence on the world food market for twenty years. However, the U.S. made no secret of the fact that it was also using food aid strategically to keep countries in the Western sphere of influence so that they would not turn communist. Far from solving the problem of world food insecurity food aid sometimes made it worse. Often the American surplus crops would depress food prices so significantly in recipient countries that indigenous farmers couldn’t compete. Governments receiving food aid below market cost had no incentive to improve agriculture in their own countries. Additionally, the commodity crops that were surplus in the United States weren’t necessarily what people were used to eating in their traditional diets, such as when wheat was sent to a country that traditionally ate rice. In some cases, people preferred the American grains to their native crops and became dependent on foods that they couldn’t grow themselves.

Despite these flaws, it seemed that the world food problem had been solved—for a while. But fears about overpopulation leading to hunger and unrest would continue to influence American thought and policy for the remainder of the 20th century—and even today. When I and other college students were told that it was our job to feed nine billion people by 2050, no one even mentioned Boyd Orr, Malthus or the Cold War. Whether my instructors realized it or not, however, their idea was a direct legacy of the hopes and fears about world hunger that started in the 1940s.

(This article first appeared in Acres USA.)

REFERENCES

1. Abbott, A. Feeding the world: Malthusian ideas in American agriculture. Wise Traditions. 2020;21(3):82-86.

2. Boyd Orr, J. As I Recall: The 1880’s to the 1960’s. Macgibbon & Kee, 1966.

3. Boyd Orr, J. Minerals in Pastures and their Relation to Animal Nutrition. London: Lewis, 1929.

4. Boyd Orr, J. Food Health and Income: Report on a Survey of Adequacy of Diet in Relation to Income. London: Macmillan, 1937.

5. Boyd Orr, J. Food and the People. London: The Pilot Press, 1943.

6. Pett, LB. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Can J Public Health. 1946;37(1):12-16.

7. Pearson FA, Harper FA. The World’s Hunger. Cornell University Press, 1945.

8. Burch GI, Pendell E. Population Roads to Peace or War. Penguin Books, Population Reference Bureau, 1947.

9. Perkins JH. Geopolitics and the Green Revolution: Wheat, Genes, and the Cold War. Oxford University Press, 1997.

10. Kellogg CE. Food production potentialities and problems. Journal of Farm Economics. 1949;31(1 Pt 2):251-262.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly journal of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Winter 2020

🖨️ Print post

Leave a Reply