🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

Chances are, if you are not obese yourself, you know someone who is. Nearly two-fifths (38 percent) of all adults in the U.S. are obese, as are over 17 percent of all American youth between two and nineteen years of age.1 The weight picture is even worse—more than two in three U.S. adults—for overweight and obesity combined.

Public health experts have bravely tried to put a positive spin on the deteriorating situation by noting, for example, an apparent leveling off of childhood obesity rates.1 They also observe that while the U.S. has the reputation of being the world’s fattest nation, a handful of other countries (including our neighbor, Mexico) actually are even heavier. Nonetheless, even as they celebrate minor progress in tackling obesity, these experts concede that obesity rates are “alarmingly higher than they were a generation ago.”1

Body mass index (BMI) is the standard tool that clinicians use to screen for obesity. BMI divides a person’s weight (in kilograms) by their height squared (in meters). As a sad reflection of the current state of affairs, “obesity” alone is no longer an adequate descriptor. Instead, experts use BMI to parse obesity into subcategories. Individuals with a BMI of thirty to less than thirty-five are in Class 1, those with a BMI of thirty-five to less than forty are in Class 2, and a BMI greater than forty (Class 3) encompasses those who carry the distinction of falling into the category of “severely” or “morbidly” obese.2

THE OMNIPRESENT INGREDIENT

Fast food and soda are two of the culprits that health professionals most commonly blame for the obesity epidemic that is unfolding not just in the U.S. but worldwide. Most nutritionists focus their attention on the calories and sugar contained in these items but are far less likely to discuss the biochemical effects of other ingredients. Scandalously, regulatory authorities and the public health community mostly continue to give a pass to one prominent and powerful ingredient: processed free glutamic acid, also known as monosodium glutamate or MSG.

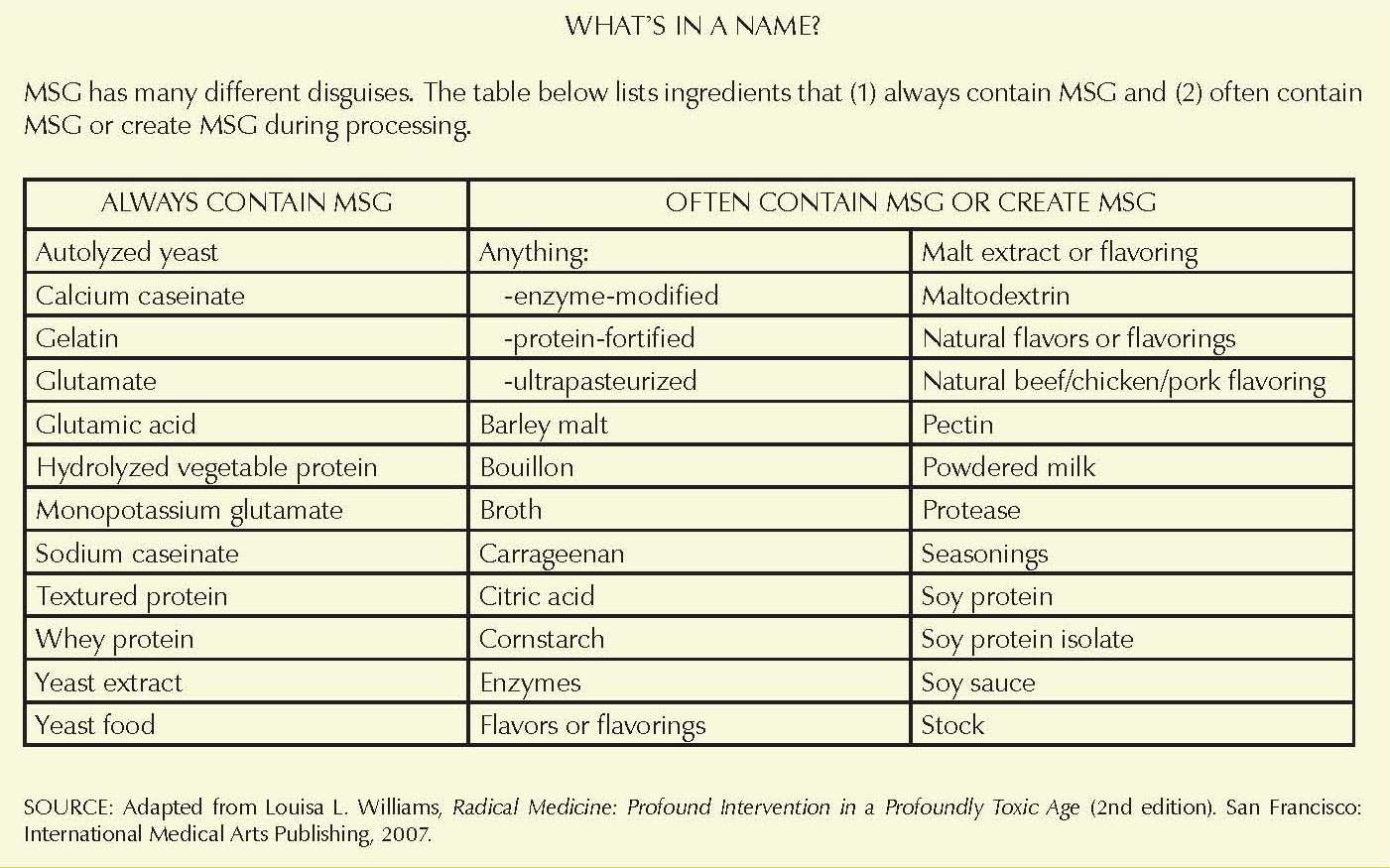

MSG labeling is complex (see “What’s in a name?”) and also outright deceptive. Due to food industry shenanigans, even foods marketed as having “no added MSG” can contain high levels of the neurotoxic substance. Not surprisingly, it is common to encounter MSG-laden ingredients at fast food restaurants (KFC is a particular offender); some of the worst offenders include chicken, sausage, “Parmesan cheese” (often a completely fake product), ranch dressing, croutons, dipping sauces, gravies and any menu item containing soy sauce, natural flavors, autolyzed yeast or hydrolyzed protein.3 Simply avoiding fast food is not enough, however, because MSG is also present in a shocking array of store-bought processed foods and brands, including most Kraft products; Campbell’s, Lipton and Progresso soups; Boar’s Head cold cuts; Planters salted nuts; and Braggs liquid aminos.3

Michael Pollan stumbled onto the hidden presence of MSG in fast food when he started tracking the trajectory of commodity corn from America’s heartland into the industrial food chain, a journey described in his best-selling book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma. According to Pollan, food chemists have been only too happy to break down and rearrange corn into hundreds of compounds that include MSG and MSG proxies such as maltodextrin and citric acid.4 When Pollan shared a McDonald’s meal with his family at the end of his corn pilgrimage, he learned that the grilled chicken breast featured in his wife’s Cobb salad—chosen because she perceived the salad to be healthier than other menu options—had been injected with a “flavor solution” containing corn-derived maltodextrin and dextrose in addition to straight MSG.4

As Pollan’s findings indicate, MSG plays a starring role in the arsenal of tricks that the fast food industry employs to enhance its products’ mouthfeel.5 According to MSG Truth, an independent research website founded by a former food industry insider, MSG ensures repeat customers by forcing the release of insulin, even in the absence of carbohydrates; the flood of insulin provoked by MSG causes an individual’s blood sugar to drop, with the result that the person feels hungry again barely an hour later.6 Moreover by strongly enhancing the perceived taste of food, MSG generates a “rush” and activates pleasure centers in the brain.6 According to Dr. Russell Blaylock, an expert on MSG and other excitotoxins (chemicals that prematurely burn out cells), the activation of pleasure centers “can produce the same powerful addiction impulse as cocaine and other addictive drugs”; as a result, hunger and addiction converge to push junk food junkies to keep on eating.7

MSG AND OBESITY

A 2010 study in Nature Neuroscience, which explored the “common neurobiological underpinnings” of heroin addiction and compulsive junk food consumption, compared rats fed a standard “nutritious” rat chow (control group) with rats fed highly “palatable” junk foods such as Ho Hos and cheesecake (experimental group).8,9 The study found that the junk-food-eating rats became compulsive eaters, taking in twice the amount of calories as the rat chow group, and they became obese. Perhaps most alarmingly, when the investigators changed the obese rats’ diet from junk food back to rat chow, the obese rats’ dietary preferences had been altered to such an extent that they refused to eat for two weeks.10

The Nature Neuroscience study did not explicitly focus on MSG, but because of the omnipresence of processed free glutamic acid, it is more than likely that the foods fed to the experimental group contained MSG. Moreover, the study dovetails with many animal studies that have used MSG to intentionally induce obesity in rodents for research purposes and particularly to study diabetes.11-13 As the authors of one recent mouse study note, “The obesity induced by neonatal treatment with monosodium L-glutamate (MSG) is an interesting tool to study the effects of obesity and diabetic condition on different metabolic parameters.”14

Like the 2010 rat experiment with junk food, other rodent studies confirm that animals treated with MSG develop new eating preferences, consuming “significantly more carbohydrate and less protein” than non-MSG-treated animals.15 Lest someone question the relevance of animal models for our understanding of MSG’s effects on human health, one writer notes that “of all the mammals, humans are the most susceptible to physical damage from ingested MSG,” with a sensitivity “five times greater than the mouse and twenty times greater than the rhesus monkey.”16 Research in humans confirms the finding that in people with a high intake of MSG, “appetite becomes more or less uncontrollable.”17 Additionally, MSG’s alarming neurotoxic effects are cumulative.18-21

It is one thing to talk in the abstract about compulsive overeating or to have wonky policy discussions about modifying “obesogenic” physical environments,22 but it is quite another thing to consider obesity from the perspective of an obese individual’s lived experiences. In his unique and eye-opening book, A Life Unburdened: Getting Over Weight and Getting on with My Life,23 Richard Morris takes his readers into “a day in the life of a fat man,” eloquently evoking the chronic and nagging distress and dissatisfaction that typify an obese person’s day-to-day life. Morris says:

Fat people live in an entirely different world…where the pull of gravity exerts a greater-than-normal toll on the body. The sun is hotter, even in winter, and the air is always thinner. In a twist of bitter irony, everything is smaller…cars, bathrooms, restaurant booths, even clothing seem designed to create the maximum amount of discomfort. The chief preoccupation…is the neverending search for contentment.

Morris observes that weight loss authorities often cast the obese as the “villains,” “gluttons” and “idle sinners” in “life’s play,” even though most overweight people share an “unshakable faith [in] the next diet, the next food fad or the next medical miracle.” By the time he was in his forties, Morris’s weight had climbed to over four hundred pounds despite being an avid runner, hiker, “gym rat” and repeat dieter. Ultimately, the transformational weight loss solution that made a difference for Morris’s household was simply to eliminate all processed foods, including foods containing MSG.

MORBID OBESITY

Morris was, by his own admission, morbidly obese, sharing that status with almost 7 percent of U.S. adults (as of 2010).24 Between 2000 and 2010, the prevalence of Class 3 morbid obesity (a BMI over forty) rose by 70 percent—and rose even faster for individuals with a BMI greater than fifty.24 Researchers admit that the morbidly obese have “more complex health issues” and also face greater challenges interfacing with the health care system than individuals with a lower BMI.25 In fact, studies have mushroomed on the topic of provider interactions with morbidly obese patients, such as a recent ethnography focusing on “managing social awkwardness when caring for morbidly obese patients in intensive care.”26 According to an employment sector white paper, federal courts also increasingly are recognizing morbid obesity as a medical condition that “impairs major life activities” and therefore has the potential to become a protected disability as defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).27

Surprisingly, a 2015 article in Obesity Science and Practice seems to exonerate the role of junk food as a contributor to obesity.28 (However one of the two authors discloses a conflict of interest as a member of McDonald’s Global Advisory Council.) The article makes the argument that for 95 percent of Americans intake of what the authors benignly call “indulgent foods” (fast food, soft drinks and candy) is unrelated to BMI.28 Buried within the article, however, are two interesting methodological details. First, the investigators confess that because they measured “number of eating episodes” rather than “amount eaten,” there is a possibility that the amount consumed per eating episode might be “higher among those with greater BMI” and is deserving therefore of further examination. In their primary analyses, the authors also excluded the “extremes”—defined as morbidly obese as well as clinically underweight individuals—because the two extreme subgroups “skewed” the data. By implication, it seems apparent that intake of unmeasured quantities of “indulgent foods” has something to do with BMI after all, at least in the most severely obese individuals.

Interestingly, some observers have noted that the MSG-obesity link “holds true even when excess calories are accounted for,”20 which suggests that MSG’s biochemical impact is more complex than a simple dose-response relationship can explain. This makes sense when one recalls that the obese rats who were exposed to MSG not only ate twice as many calories as unexposed rats but also manifested dramatic changes in their eating habits, preferentially focusing on carbohydrates. On the other hand, Richard Morris describes how the overweight often become desperate enough to eat “just about anything, whether we like it or not.”

THE BOTTOM LINE

Despite knowing about the harmful effects of MSG for decades, the Food and Drug Administration and the processed food industry have worked hard to keep this information out of the limelight.29 Who should now be held accountable for the economic and public health fallout of MSG-induced obesity?30 Although the fast food industry has endured lawsuits pertaining to trans fats, it generally has managed to hold at bay any legal actions establishing a link between fast food and obesity. Judging by the legislative actions currently the focus of debate at the state level, which range from restricting soda sales in schools to charging obese individuals higher insurance premiums,31 no one appears to have much willingness to go after the food industry and persuade food chemists to stop using MSG.

From the industry’s perspective, there is little incentive to modify current practices. Because “the anticipated result of MSG flavor enhancement is that we eat more of the MSG-enhanced foods,” MSG is a boon that creates more profits for the companies that supply these foods.32 From the perspective of diet-weary and ever fatter consumers, on the other hand, it is clear that MSG is a boondoggle. Regardless of MSG’s exact mechanisms of action on weight, it is apparent that eliminating processed flavor-enhanced foods from one’s diet is a wise and essential course of action.

SIDEBARS

BEWARE ASPARTAME

Many overweight and obese individuals turn to diet soda in an effort to cut down on sugar and calories. However

aspartame, like MSG, is an excitotoxin and neurotoxin, and like MSG, aspartame is associated with weight gain.33 Studies suggest that aspartame stimulates appetite and increases carbohydrate cravings and fat storage.34 A physician who understands the effects of aspartame notes that aspartame “muddles the brain chemistry” by blocking production of serotonin, which plays a key role in controlling food cravings.35 In addition, the two amino acids that make up 90 percent of aspartame (phenylalanine and aspartic acid) stimulate the release of insulin and leptin, the primary hormones regulating metabolism.34 As one writer describes it, when the body “discovers it was cheated out of food, it revolts by throwing a food-craving tantrum that can only be quelled by eating blood sugar food that will more than likely be high-calorie sugary snacks.”35 Dr. Joseph Mercola describes aspartame as the most dangerous food additive on the market today.36

MSG IN VACCINES

Although the focus of this article is on the MSG in processed food, a lesser-known fact is that pharmaceutical companies use MSG as a stabilizer in some vaccines to protect against product exposure to heat, light, acidity and humidity.37 Five vaccines contain MSG: adenovirus, influenza (FluMist) quadrivalent, MMRV (ProQuad), varicella (Varivax) and zoster (Shingles-Zostavax).38 No testing has been conducted on the short-term or long-term safety of injecting MSG into the body in this way, nor has any scientific or regulatory body examined potential adverse interactions between MSG and other vaccine ingredients).38

REFERENCES

1. Segal LM, Rayburn J, Martin A. The state of obesity 2016: better policies for a healthier America. Washington, DC, and Princeton, NJ: Trust for America’s Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining adult overweight and obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html.

3. MSG Truth. Foods to avoid. http://www.msgtruth.org/avoid.htm.

4. Pollan M. The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

5. Schlosser E. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. New York: Perennial, 2002.

6. MSG Truth. What exactly is MSG? http://www.msgtruth.org/whatisit.htm.

7. Blaylock R. MSG: The hidden addiction. Newsmax, September 17, 2014.

8. Johnson PM, Kenny PJ. Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Nat Neurosci 2010;13:635-641.

9. Sanders L. Junk food turns rats into addicts. Science News, October 21, 2009.

10. Waddell G. New scientific data shows “junk food is addictive and causes obesity!” – Tell me something we don’t already know. Fitmontclair Blog, April 18, 2010.

11. Bunyan J, Murrell EA, Shah PP. The induction of obesity in rodents by means of monosodium glutamate. Br J Nutr 1976;35(1):25-39.

12. Sanches JR, França LM, Chagas VT et al. Polyphenol-rich extract of Syzygium cumini leaf dually improves peripheral insulin sensitivity and pancreatic islet function in monosodium Lglutamate-induced obese rats. Front Pharmacol 2016;7:48.

13. Pelantová H, Bártová S, Anyz J et al. Metabolomic profiling of urinary changes in mice with monosodium glutamate-induced obesity. Anal Bioanal Chem 2016;408(2):567-578.

14. Martin JM, Miranda RA, Barella LF et al. Maternal diet supplementation with n-6/n-3 essential fatty acids in a 1.2:1.0 ratio attenuates metabolic dysfunction in MSG-induced obese mice. Int J Endocrinol 2016;2016:9242319.

15. Kanarek RB, Marks-Kaufman R. Increased carbohydrate consumption induced by neonatal administration of monosodium glutamate to rats. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 1981;3(3):343-350.

16. Waddell G. MSG causes obesity and you won’t believe where it is hiding! Fitmontclair Blog, March 31, 2010.

17. Renter E. Researchers link MSG to weight gain, obesity. Natural Society, February 24, 2013.

18. Blaylock RL. Excitotoxins: The Taste that Kills. Albuquerque, NM: Health Press, 1996.

19. Lorden JF, Caudle A. Behavioral and endocrinological effects of single injections of monosodium glutamate in the mouse. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 1986;8(5):509-519.

20. Nikoletseas MM. Obesity in exercising, hypophagic rats treated with monosodium glutamate.

Physiol Behav 1977;19(6):767-773.

21. Tawfik M, Al-Badr N. Adverse effects of monosodium glutamate on liver and kidney functions in adult rats and potential protective effect of vitamins C and E. Food Nutri Sci 2012;3(5):651-659.

22. Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S et al. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health 2014;14:233.

23. Morris, Richard. A Life Unburdened: Getting Over Weight and Getting on with My Life. Washington, DC: New Trends Publishing, 2007.

24. Sturm R, Hattori A. Morbid obesity rates continue to rise rapidly in the United States. Int J Obes 2013;37(6):889-891.

25. Keaver L, Webber L. Future trends in morbid obesity in England, Scotland, and Wales: a modelling projection study. Lancet 2016;388(Suppl 2):S1-S116.

26. Hales C, de Vries K, Coombs M. Managing social awkwardness when caring for morbidly obese patients in intensive care: a focused ethnography. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;58:82-89.

27. Employment Practices Solutions (EPS). Obesity and morbid obesity in the workplace: ADA trends and best practices. Coppell, TX: EPS, 2004.

28. Just D, Wansink B. Fast food, soft drink, and candy intake is unrelated to body mass index for 95% of American adults. Obes Sci Pract 2015;1(2):126-130.

29. Offer A. The cover-up of hidden MSG. Natural News, December 12, 2008.

30. Mello MM, Rimm EB, Studdert DM. The McLawsuit: the fast-food industry and legal accountability for obesity. Health Aff 2003;22(6):207-216.

31. Longley R. Big brother, thinner brother: can legislation prevent obesity in America? About.com, May 17, 2016.

32. Vicki. MSG free, it’s not as clear as it seems. Organic Authority, June 29, 2007.

http://www.organicauthority.com/health/health/msg-free-its-not-as-clear-as-it-seems.html.

33. Morell SF. Diet sodas and weight gain. October 31, 2014. https://www.westonaprice.org/uncategorized/diet-sodas-and-weight-gain/.

34. Mercola J. Artificial sweeteners cause greater weight gain than sugar, yet another study reveals. Mercola.com, December 4, 2012.

35. Ephraim R. Aspartame: diet-astrous results. The Weston A. Price Foundation, May 26, 2002.

36. Mercola J. Aspartame: by far the most dangerous substance added to most foods today. Mercola.com, November 6, 2011.

37. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ingredients of vaccines–fact sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/additives.htm.

38. Parpia R. Monosodium glutamate used as a stabilizer in vaccines. The Vaccine Reaction, June 16, 2016.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly magazine of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Spring 2017.

🖨️ Print post

One of the most informative articles I’ve read on MSG. I have a severe intolerance for MSG– I get debilitating migraine headaches. I am so resentful of the food industry. They are poisoning us. I cook all my own food now– nothing processed. Thank you Merinda for this great information. MSG is toxic for all of us. Thank you for enlightening us to the relationship of MSG to obesity.

I switched from soy sauce to Braggs liquid aminos, thinking I was making a healthy swap. Can you inform me why that is not a good choice, and what to use in its place? Thank you!

Monosodium glutamate is a salt form of one of the amino acids. When glutamate is freed from its source protein, it acts as an excitotoxin on the brain, tricking the brain into thinking what you’re eating is really good and leading to the problems discussed in the article (or worse for some of us). So anytime you break out the amino acids from the source protein, you get something similar to MSG. That’s why the ingredient list in the article is really based on free glutamic acid vs simply MSG and has things like protein isolates on it. In my case, my body reacts to MSG as if I have been poisoned but I seem to do fine with a little soy sauce and eating ‘no MSG’ Chinese restaurant foods.