🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

Albert Einstein once coined the phrase “combinatory play” to describe the process of taking unrelated elements and concepts and putting them together to generate new ideas. Einstein did not invent the concepts of energy, mass or speed of light for his famous equation. Rather, he combined these concepts in a novel way, which restructured the way he looked at the universe.

In similar fashion, I have drawn from several different bodies of knowledge about the glutamate molecule (also called glutamic acid) to make the case that ingestion by humans of manufactured free glutamate—including the flavor-enhancing food additive monosodium glutamate (MSG), the sodium salt of glutamic acid—is at the root of the obesity epidemic. The glutamate-obesity link stems from the following well-established facts: free glutamate is prevalent in the diet due to its presence in most processed foods; given its dietary prevalence, pregnant and lactating women routinely expose fetuses and newborns to free glutamate via the placenta and breast milk; and, under some circumstances, free glutamate induces brain damage affecting the part of the brain that controls food intake and metabolism.

Glutamate is the principal neurotransmitter in humans, carrying nerve impulses from glutamate stimuli to glutamate receptors throughout the body. However, it is also widely recognized as a “Jekyll and Hyde” amino acid.1,2 When present in protein or released from protein in a regulated fashion through routine digestion, glutamate is vital for normal body function. On the other hand, when present in greater quantity than a healthy human needs for normal body function, it becomes toxic. In that instance, as an “excitotoxic” neurotransmitter, it fires repeatedly, damaging targeted glutamate receptors and/or causing neuronal and non-neuronal death by overexciting the glutamate receptors until their host cells die.3

THE RISE OF FOOD EXCITOTOXINS

In the 1990s, the first edition of the book Excitotoxins: The Taste that Kills by Dr. Russell Blaylock drew the public’s attention to neurotoxic food additives, which had already been in use for decades. As that book put it, an excitotoxin “literally stimulates neurons to death, causing brain damage of varying degrees.”4

MSG is one of the most well-known excitotoxins. MSG’s ongoing heyday began in 1957, when food scientists shifted from a slow and costly method that called for extraction of free glutamate from a protein source, to bacterial fermentation as a “new and improved” method for the production of free glutamic acid for use in food. From that point forward, the virtually unlimited production of free glutamate was guaranteed.

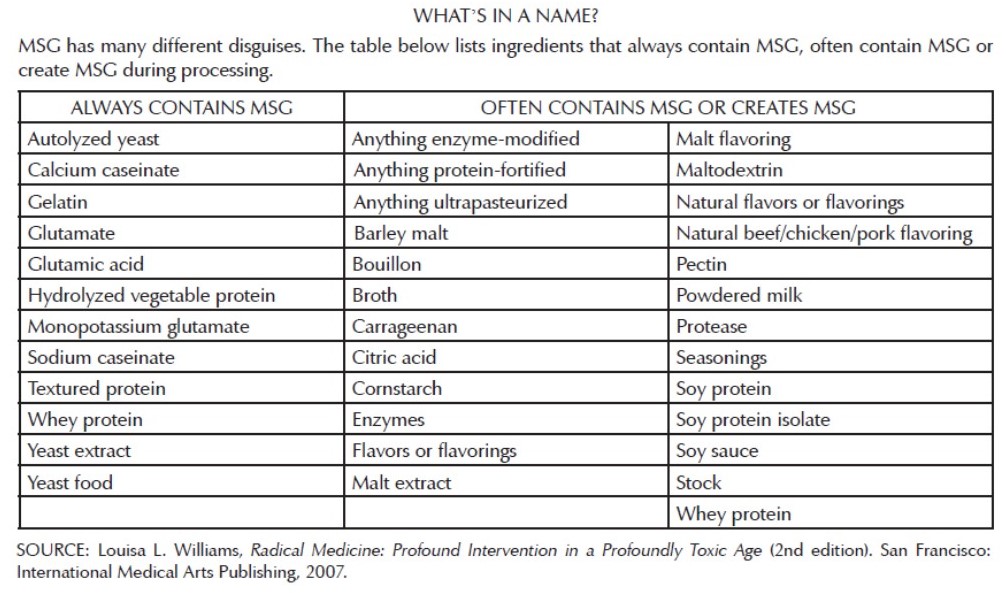

Following the surge in MSG and free glutamate production, boosted by aggressive advertising, many companies recognized that profits could be increased if they produced their own flavor-enhancing additives. It wasn’t long before competing manufacturers were adding dozens more excitotoxic food additives to the American diet. Companies soon flooded the market with flavor enhancers and protein substitutes containing free glutamate—ingredients such as hydrolyzed pea protein, yeast extracts, maltodextrin and soy protein isolate, as well as MSG.5,6 A further toxic load was added to that list when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the excitotoxin aspartic acid, used beginning in 1974 in aspartame, Equal® and related products.

According to Dr. Blaylock, the amount of MSG added to the food supply has doubled every decade since the late 1940s.7

SETTING THE STAGE FOR NEUROTOXICITY

Although I knew a great deal about the toxic effects of MSG, it was only as people began reporting adverse reactions following ingestion of foods that did not contain MSG that I realized it was the free glutamate in MSG—and in flavor enhancers other than MSG—that was causing what consumers were calling “MSG reactions.”

There is no question that free glutamate ingestion does cause adverse reactions. Some scientists claim that it elicits transient adverse reactions only in a small subset of people sensitive to the substance. Others maintain, however, that it causes adverse reactions on a broader scale, ranging from simple skin rash to migraine headache,8 heart irregularities, seizures and anaphylactic shock. Despite what is known about adverse reactions and the potential for brain damage, FDA imposes no limits on the amount of either MSG or free glutamate that a single food ingredient may contain.

Research shows that three conditions must be met in order to induce glutamate neurotoxicity. The first important factor is the integrity and health of the brain. Harm is most likely to occur when the brain is vulnerable, meaning either immature—such as the fetal or neonate brain—or damaged. A fetus will be even more vulnerable to glutamate insult than a newborn.

Second, a sufficient quantity of free glutamate must be present to enable it to become excitotoxic. Since the 1957 change in the method of MSG production, so many products contain excitotoxic ingredients that it is easy for a consumer to ingest an excess during in a day.9-12

Today, there is sufficient excitotoxic free glutamate in processed foods, dietary supplements, snacks, protein powders, protein drinks, protein substitutes, baby formula, enteral care products and pharmaceuticals for a person to consume the quantity necessary for that free glutamate to become excitotoxic.

Third, the excess glutamate must be delivered to the vulnerable brain. In children and adults, delivery of free glutamate to a vulnerable brain can be achieved simply through the person consuming a sufficient quantity of free glutamate to cause it to be excitotoxic. In fetuses and neonates, delivery of excitotoxic free glutamate will be achieved when a pregnant or lactating female passes brain-damaging excess free glutamate through the placenta or in mothers’ milk. There is nothing to prevent ingested glutamate from entering immature brains.

DELIVERY VIA PLACENTA AND BREAST MILK

Pregnant women deliver nourishment (and not so nourishing material) to the fetus in the form of material ingested and passed through the placenta. Studies show that MSG can cross the placenta.13,14 In other words, when glutamate passes to the fetus, the placenta does not filter out the glutamate.13 Research also indicates that MSG can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in an unregulated manner during development; the BBB is not fully developed in either the fetus or the newborn. The BBB is easily damaged not just by ingestion of MSG but also other factors such as fever, stroke, trauma to the head, seizures and the aging process.1,15

MSG can also pass through the five circumventricular organs—specialized structures located along the surface of the brain ventricles.16 The circumventricular organs lie outside the BBB and are leaky at best at any stage of life,17,18 meaning they are not impervious to glutamate-induced brain damage.

Similar to drugs and alcohol,19 free glutamate can be passed to infants through mothers’ milk. The glutamate in mothers’ milk will be excitotoxic if lactating mothers ingest excessive quantities of free glutamate—quantities sufficient to cause the free glutamate to become excitotoxic. Newborn humans may also receive free glutamate through infant formula, which routinely contains ingredients featuring free glutamic acid and free aspartic acid.20

THE RISE OF OBESITY

In 1969, Dr. John Olney demonstrated that the glutamic acid component of MSG, when administered in high doses to mice, caused brain damage in various parts of the brain, including the arcuate nucleus (AN) of the hypothalamus, one of the circumventricular organs.21 (Recall that the circumventricular organs are outside the blood-brain barrier.) Neurocircuitries in the AN control multiple physiological functions, including regulating food intake and glucose homeostasis, and “disruption of this fine-tuned control leads to an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure as well as deregulation of peripheral metabolism.”22 Given the AN’s critical metabolic role, it is not surprising that Olney’s study went on to find that the glutamate-induced brain lesions led to “marked obesity” when the mice reached adulthood, as well as stunted skeletal development and female sterility.

In the decade that followed, others replicated Olney’s work, confirming that free glutamate fed to infant animals causes brain lesions in the arcuate nucleus, followed by gross obesity.23 In the 1970s, scientists employed by the glutamate industry challenged Olney’s findings, conducting studies that ostensibly failed to replicate glutamate-induced brain damage. However, it soon became apparent that these studies were industry-sponsored—designed to guarantee that no traces of glutamate-induced brain damage would be found.

Around 2016, I began thinking about the unexplained obesity epidemic and reading about the adverse effects of ultra-processed foods. I realized that because these highly processed foods were made of cheap ingredients and chemicals, they would necessarily contain flavor enhancers to compensate for the lack of flavor—with all of those flavor enhancers containing excitotoxic free glutamate. I also knew that after the late 1950s, essentially unlimited amounts of free glutamate were at processed food manufacturers’ disposal.

Knowing that glutamate fed in large amounts to animals with immature brains causes brain damage followed by gross obesity, and knowing that the brains of fetuses and neonates are vulnerable to glutamate insult, I reasoned that if glutamate in large amounts could be “fed” to human fetuses and neonates, brain damage and obesity would follow. With the proliferation of processed and ultra-processed foods, there was little doubt in my mind that there is sufficient free glutamate in most pregnant women’s diets to provide the “excess” glutamate needed to cause the glutamate ingested to become excitotoxic (brain-damaging), particularly if more than one glutamate-containing ingredient is consumed during the course of a day. It also occurred to me that if a pregnant woman consumed free glutamate in excess of what she needed for normal body function, the excitotoxic excess would be passed not just to the fetus through the placenta but later to the infant while nursing.

In short, the onset of the modern obesity epidemic can be traced back to the introduction of excessive amounts of free glutamate made available to humans following the modernization of MSG manufacture in 1957. The obesity exhibited in some individuals as they reach maturity can be linked to the excitotoxic amino acids ingested by their mothers when pregnant and lactating.

Once one understands the fact that excitotoxins are readily available to most pregnant women and new mothers, it is easy to grasp how these toxins are transported to the fetus and newborn where they cause brain damage, which in turn causes obesity. Consequently, excitotoxic amino acids delivered to fetuses and neonates by pregnant and nursing women should be recognized as risk factors for obesity.

Acknowledgment of the fact that glutamate-induced brain damage in fetuses and neonates lies at the root of the obesity epidemic should put an end to the shame and blame that have long been associated with obesity and should facilitate appropriate counseling and medical interventions. It should also serve as a valid starting point for new groundbreaking research.

LOOKING THE OTHER WAY

In this article, I have accounted for all five pieces to the puzzle of the obesity epidemic:

- The concept of excitotoxicity, with free glutamate being the principal excitotoxin;

- The fact of glutamate-induced brain damage followed by obesity;

- The abundance of excitotoxic glutamate in processed and ultra-processed foods;

- The fact that pregnant females can pass excitotoxic glutamate to their fetuses; and

- The correlation between the time that virtually unlimited amounts of free glutamate became available in food and the beginning of the obesity epidemic.

Nonetheless, ever since the first suggestion that MSG might have toxic potential, those with a financial interest in promoting MSG as a cheap and valuable flavor enhancer have denied its toxicity, launching well-funded, well-articulated campaigns to promote their products. Industry responses also include rigging studies to come to the foregone conclusion that MSG is a harmless food additive, and securing the active cooperation of regulators as well as the help of medical professionals, many of whom appear to be more than happy to look the other way.24 These actions may explain why the role of MSG and manufactured free glutamate in the obesity epidemic continues to be overlooked.

In 1950, Americans consumed about one million pounds of MSG; today, that number is three hundred million pounds. Given that almost all processed food and fast food contains MSG (usually not labeled),6 the food industry certainly knows that the additive they use to make their food taste good is a major cause of the current obesity epidemic. The message to consumers is clear: to lose weight, it’s important to avoid all processed food, and certainly not add MSG to the foods you prepare at home.

SIDEBAR

MSG PROPAGANDA

In August 2021, the Washington Post published a puff piece on MSG, claiming that we have nothing to fear from the artificial flavoring that adds umami “spark” to many dishes.25 The author, Aaron Hutcherson, marginalized headaches and allergic reactions as minor symptoms in a few hypersensitive people. Said Hutcherson: “In addition to soup and eggs, MSG can be added to salad dressings, bread, tomato sauce, meats, popcorn, ‘an absolutely filthy martini,’ you name it. MSG is a great way to add flavor to just about anything except sweets. It’s particularly great with vegetables, too.”

He made no mention of the real problem with MSG: weight gain. If you search “msg-induced obesity” at PubMed, you will come up with almost one hundred citations. Most of the citations are animal studies, not human trials. This is because it’s hard to get research animals to overeat and become obese—in order to study obesity—so scientists feed rats, mice and hamsters MSG to make them eat more and put on weight. The food industry has argued that the amount of MSG given to these animals is way more, as a function of body weight, than humans would ever eat. Or, they say, the association with weight gain and MSG is really an association of weight gain and processed foods, since MSG is in almost all processed foods.

What happens when we consume small amounts of MSG as a flavoring day after day after day? A 2008 study published in the journal Obesity provides confirmation that MSG indeed causes weight gain in humans, and not because of its inclusion in processed foods.26 In this well-designed trial, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill studied seven hundred fifty Chinese men and women, ages forty to fifty-nine, living in three rural Chinese villages. Most of the study subjects prepared their meals at home without commercial processed foods, and about 82 percent used MSG. Those participants who used the highest amounts of MSG had nearly three times the incidence of overweight as those who did not use MSG, even when the researchers accounted for physical activity and caloric intake.

What about the argument, made by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and quoted by Hutcherson in The Washington Post article, that “The glutamate in MSG is chemically indistinguishable from [the essential amino acid] glutamate present in food proteins”? This sentence is true, but the FDA’s and Hutcherson’s second assertion—that “Our bodies ultimately metabolize both sources of glutamate in the same way”—is false. The glutamic acid in foods like meat is attached to various peptides and other compounds that release it when required and prevent it from overstimulating the nervous and endocrine systems; the glutamic acid in MSG, in contrast, is “naked,” highly reactive and unmitigated by its milieu.

REFERENCES

- Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ. Dietary glutamate and the brain: In the footprints of a Jekyll and Hyde molecule. Neurotoxicology. 2020;80:93-104.

- Morley WA, Seneff S. Diminished brain resilience syndrome: A modern day neurological pathology of increased susceptibility to mild brain trauma, concussion, and downstream neurodegeneration. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:97.

- Excitotoxicity and cell damage. https://www.sciencedaily.com/terms/excitotoxicity.htm

- Blaylock RL. Excitotoxins: The Taste that Kills. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Health Press, 1994.

- Teller M. MSG: Three little letters that spell big fat trouble. Wise Traditions. Spring 2017;18(1):42-46.

- Morell SF. MSG and free glutamate: Lurking everywhere. https://nourishingtraditions.com/msg-free-glutamate-lurking-everywhere/

- Blaylock RL. Excitotoxins, neurodegeneration and neurodevelopment. Available at: http://landofpuregold.com/the-pdfs/Excitotoxins.pdf.

- Interview with Jodi Ledley. Weston A. Price Foundation, Aug. 10, 2018. https://www.westonaprice.org/health-topics/interview-with-jodi-ledley/

- Global monosodium glutamate market poised to surge from USD 4,500.0 million in 2014 to USD 5,850.0 million by 2020. Market Research Store, Mar. 17, 2016. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2016/03/17/820804/0/en/Global-Monosodium-Glutamate-Market-Poised-to-Surge-from-USD-4-500-0-Million-in-2014-to-USD-5-850-0-Million-by-2020-MarketResearchStore-Com.html

- Global flavor enhancers market. BCC Research, Dec. 2018. https://www.bccresearch.com/partners/verified-market-research/global-flavor-enhancers-market.html

- Global food flavor enhancer market by type (monosodium glutamate (MSG), hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP), yeast extract others), by application (restaurants, home cooking, food processing industry) and by region (North America, Latin America, Europe, Asia Pacific and Middle East & Africa), forecast to 2028. Dataintelo, n.d. https://dataintelo.com/report/food-flavor-enhancer-market

- Sano C. History of glutamate production. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):728S-732S.

- Frieder B, Grimm V E. Prenatal monosodium glutamate (MSG) treatment given through the mother’s diet causes behavioral deficits in rat offspring. Int J Neurosci. 1984;23(2):117-126.

- Yu T, Zhao Y, Shi W, et al. Effects of maternal oral administration of monosodium glutamate at a late stage of pregnancy on developing mouse fetal brain. Brain Res. 1997;747(2):195-206.

- Nemeroff CB, Crisley FD. Monosodium L-glutamate-induced convulsions: Temporary alteration in blood-brain barrier permeability to plasma proteins. Environ Physiol Biochem. 1975;5(6):389-395.

- Benarroch EE. Circumventricular organs: Receptive and homeostatic functions and clinical implications. Neurology. 2011;77(12):1198-1204.

- Price MT, Olney JW, Lowry OH, Buchsbaum S. Uptake of exogenous glutamate and aspartate by circumventricular organs but not other regions of brain. J Neurochem. 1981;36(5):1774-1780.

- Broadwell RD, Sofroniew MV. Serum proteins bypass the blood-brain fluid barriers for extracellular entry to the central nervous system. Exp Neurol. 1993;120(2):245-263.

- https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/vaccinations-medications-drugs/alcohol.html

- Samuels JL. MSG in infant formula. Weston A. Price Foundation, Dec. 31, 2001. https://www.westonaprice.org/health-topics/modern-foods/msg-in-infant-formula/

- Olney JW. Brain lesions, obesity, and other disturbances in mice treated with monosodium glutamate. Science. 1969;164(3880):719-721.

- Jais A, Brüning JC. Arcuate nucleus-dependent regulation of metabolism—pathways to obesity and diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2022;43(2):314-328.

- Burde RM, Schainker B, Kayes J. Monosodium glutamate: necrosis of hypothalamic neurons in infant rats and mice following either oral or subcutaneous administration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1972;31:181.

- Samuels A. The toxicity/safety of processed free glutamic acid (MSG): a study in suppression of information. Account Res. 1999;6(4):259-310.

- Hutcherson A. Why you shouldn’t fear MSG, an unfairly maligned and worthwhile seasoning. Washington Post, Aug. 27, 2021.

- He K, Zhao L, Daviglus ML, et al. Association of monosodium glutamate intake with overweight in Chinese adults: the INTERMAP study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(8):1875-1880.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly journal of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Summer 2022

🖨️ Print post

Leave a Reply