🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

Fifty years ago, chicken found its way to the dinner table once a week at most, and often even less frequently as a special occasion meal. How, in under five decades, did chicken go from being the most expensive meat to the least expensive? What happened that took the chicken from Sunday dinner to the “dollar menu special”? Let’s take a look at how science and technology transformed chicken into America’s most consumed meat.

ONCE UPON A CHICKEN

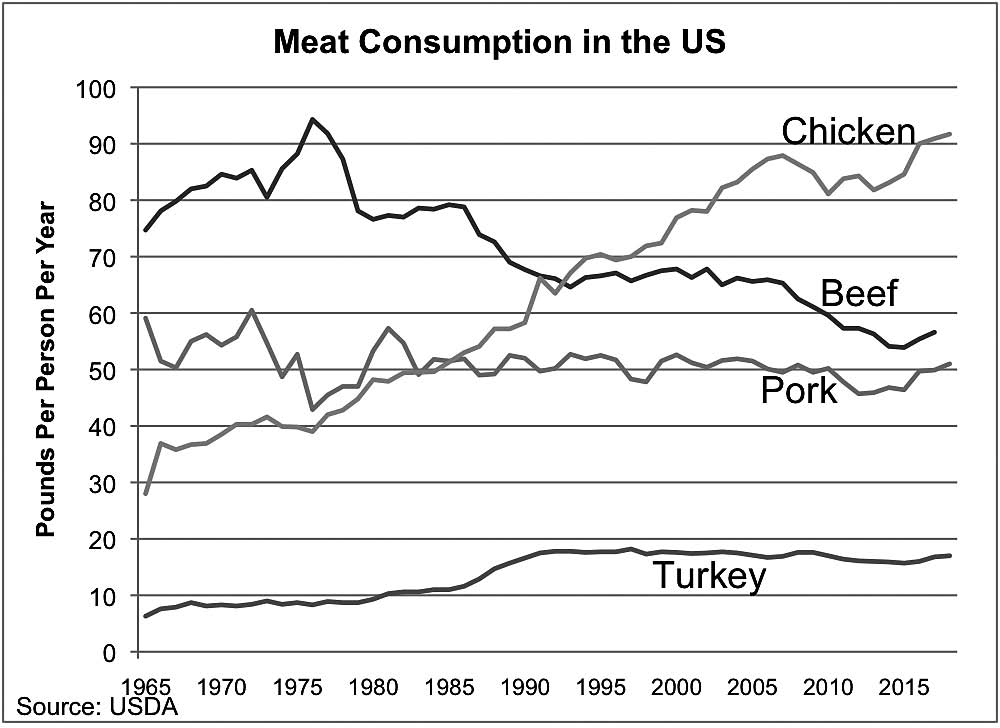

For most of American history, poultry and eggs were luxury foods. Chicken traditionally was far more expensive than beef or pork—after all, you needed grain to feed chickens, but cows could grow on grass and pigs could grow on garbage. For the first half of the twentieth century, the average person ate twenty pounds of chicken or less per year (approximately six chickens). By 1964, chicken had become more of a staple and people were consuming over a half pound per week—up to twenty-five to thirty pounds per year.1 Since then, we have continued to increase our chicken consumption almost every single year. As a result, chicken is now the number-one meat in the nation, with the average person consuming an estimated two pounds per person per week,2 or roughly one hundred pounds (thirty chickens) per year. In 2015, the average household ate chicken three to four times per week.

In 2016, America’s poultry industry produced over nine billion chickens. If the state of Georgia were its own country, it would rank as the fourth-highest country in the world for poultry production. As a result of this large-scale production, chicken has become the most affordable animal protein source at the grocery store, at times on sale for less than one dollar per pound. In contrast, beef and pork sell for around three to four dollars per pound. A prediction made in the 1940s—that chicken would become “meat for the price of bread”—has come to pass.3

A CHICKEN’S LIFE FOR ME

A lot had to change for chicken to become such a production powerhouse. Up until the mid-1900s, the majority of chickens were raised in small flocks (one to three hundred birds) on small family farms. When old laying hens retired, they became “stewing hens.” Excess young males were sold as “spring chickens.” With very little breast meat, neither of these resembled the chickens we cook today. The stewing hens were tough and required long, slow cooking to make them palatable. The spring chickens, although easier to prepare, produced a paltry two to two-and-a-half pounds of dressed bird for the dinner table. Both were extremely expensive.

On the family farm, chickens provided, at best, a little bit of side money for a farmer’s wife and kids, but the farmer certainly never considered them an enterprise of economic significance. In part, this was because mortality for chickens was high. Reduced winter forage, predation and other problems made for a tough life, especially in colder climates. One of the main problems was nutritional. Chickens develop health and disease issues during dark, cold days with scarce food. Heated coops and mountains of nutritionally fortified purchased feed were not the norm.

The 1920s ushered in a sea change for the American chicken. Scientists who were just beginning to unravel the world of nutrition discovered vitamins A and D. For a time, cod liver oil became a mainstay of the chicken’s supplemental diet, and mortality rates dropped. The incubator, invented a few decades before, also began facilitating the creation of hatcheries across the country. Incubators could (and did) supply larger and larger numbers of chicks, displacing the erratic and unpredictable on-farm replacement flock approach.4 The stage was set to transform chicken production from a small-scale side enterprise into something more economically substantial, and that is just what Cecile Steele of Delaware did.

STEELE CHICKENS

Cecile Steele holds a dubious but important place in poultry history for creating commercial poultry production. In 1923, she ordered fifty chicks, but the company sent five hundred by accident! She decided to keep them all, raising them specifically as meat birds.5 Things went so well that year and in subsequent years that by 1926, Steele had built a barn to house ten thousand birds. Two years later, she raised almost thirty thousand. Industrial chicken was born, and it quickly boomed. A decade later, Delaware alone produced seven million broilers per year.4 Although Steele’s chickens were tiny things, weighing only around two pounds, people loved them, even with their relatively high price tag. In today’s money, Steele fetched a profitable five dollars per pound for that first batch of five hundred chickens. Such high profits and prices would not last long, however, and the steady decline in chicken prices soon began.4

The changes that Steele and others made to chickens’ housing conditions required significant changes to almost everything about a chicken’s diet and life. No longer able to forage, chickens became dependent on artificial food. The timing was right because soy was beginning to provide a standardized, cheap, high-protein feed perfect for confined chickens. Founded in 1919, the American Soybean Association was very happy to have soy become, along with corn, the backbone of the burgeoning confined poultry production model.6

Although the poultry production system was starting to solidify, it would take two more decades for everything to come together and for chicken to truly take off. What was needed was the “Chicken of Tomorrow” and the tools to keep it alive. The meteoric rise of the industry that followed is rivaled only by the gargantuan size, never before seen, of the chickens that would result.

ANTIBIOTICS: BACKBONE OF BIG MEAT

If vitamins, soy for animal feed and similar advances set the stage for raising chickens in confinement, antibiotics stole the show. Moving animals off pasture and into densely populated barns created disease pressure. Artificial nutrition and supplementation could offset only a portion of this extra stress. In addition, as production increased, prices dropped, which put immense pressure on farmers to raise more with less—less space, fewer costs, less care. Questions arose about how far the industrial system could be pushed and how much chicken it could produce.

A scientist named Thomas Jukes discovered the solution to these problems: antibiotics. Working at a research facility for Lederle in the 1940s, Jukes was fixated on figuring out what would allow chickens to flourish in confinement. It was a pressing question—two world wars (with one still ongoing) had produced an incredibly high demand for protein. Although chicken production had increased immensely in just twenty years, chickens did best on vitamin-rich fish meal and other animal byproducts that were too scarce and expensive for farmers to offer to their ever larger flocks. Chickens did poorly on the cheaper soy-based substitutes, with poor weight gain for meat birds and poor egg quality for layers.

Jukes discovered that when he added antibiotics to the feed of the chickens in his experiments, they not only performed better than the other groups, but they specifically gained more weight. The birds given the greatest amount of antibiotics gained the most weight. The best part was that this strategy was cheap, adding less than a penny per pound of animal feed yet producing 25 to 50 percent gains in animal weight.3 In this way, antibiotics became the backbone and constant companion of modern meat production.

THE CHICKEN OF TOMORROW

All the pieces were now in place for chicken to shake off its “Sunday dinner” image and become the meat of choice across the country. All, that is, except the chicken itself. The birds had enjoyed a dramatic increase in weight, but they were still mostly dark meat and continued to require a great deal of preparation. Despite its continuing plunge in price, chicken was still not the first choice of the average housewife and not quite what the American family was looking for.

In the 1940s, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) organized a contest entitled “The Chicken of Tomorrow.” It was perhaps the greatest effort ever put forth by the meat industry, involving government agencies, scientists, colleges, researchers and volunteers from across the country. What was the contest’s goal? The goal was to achieve “One bird, chunky enough for the whole family—a chicken with breast meat so thick you can carve it into steaks, with drumsticks that contain a minimum of bone buried in layers of juicy dark meat, all costing less instead of more.”3

The contest winners duly delivered a chicken that was 40 percent heavier than the standard chicken (reaching a total of three and a half pounds, a full pound over the average at the time) in just eighty-six days from egg to contest’s end. This was only the beginning of the chicken’s unprecedented growth, however. Today, chickens from those same blood lines reach six pounds in under seven weeks and do so on half the amount of feed per pound of flesh. Three times the amount of meat in half the time for half the feed represents an almost unimaginable achievement. Through careful, highly secretive breeding and cross-breeding, the “chicken of tomorrow” had finally arrived.

This incredible increase in yield created a large chicken but also gave rise to an equally large problem. The chicken market was glutted, eerily foreshadowing what industrial farming would do time and time again with supply outpacing demand. However, farmers responded by raising more, not less, of the unneeded item. If farmers were not going to raise fewer chickens, people were going to need to eat more. How to convince people to eat more chicken became the new challenge.

As events unfolded, the chicken glut became an opportunity for modern marketing and for food processing gold. The poverty and deprivation of the war years turned into the prosperity and indulgence of the fifties and sixties and transformed American eating and cooking habits. Refrigerators, packaged baking mixes and all sorts of processed foods flooded the market. Chicken was not only the first meat to benefit from advances in nutrition and the application of antibiotics to animal production (along with an immense infusion of government resources and research), it also was the first meat to become the mainstay of the processed food products heavily marketed to the American people. Slick marketing convinced people to adopt these new items en masse, including an array of processed chicken products. It made only too much sense at the time—an animal living in an artificial environment and being fed artificial foods and nutrients would become the processed, artificial meat food for the masses.

THE MOST DANGEROUS MEAT

Chicken’s ascent to the top of the American diet did not come cheaply. Government involvement in the industrial production of chicken continued long after the “Chicken of Tomorrow” contest ended. The main feed stuffs for chicken—corn and soy—still enjoy multibillion dollar per year government subsidies. The USDA recently announced that 2016 payments under the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) program totaled eight billion dollars.7 This is just one of many subsidies and support programs that industrial food and meat producers enjoy at the taxpayer’s expense. Total subsidies, direct and indirect, may well run into the tens of billions of dollars per year.

With all these subsidies, one would think that chicken producers wouldn’t need to cut corners. This could not be further from the truth. Most store-bought chicken is bulked up even further through “brining”—injecting the meat with a salt-water mixture. Studies have found that this cheap mixture represents almost one-fifth of store-bought chicken by weight.8 Processed chicken products (tenders, nuggets and the like) are even worse, containing fillers, additives and extenders that sometimes comprise up to half the finished product’s weight.

Chicken’s low cost at the store hides a high price tag in terms of health. The mass production of chicken (as well as pork and, to a lesser extent, beef), has unleashed a microbiological war. Although antibiotics quickly became an industry crutch in both “growth promotion” and “mortality reduction,” as early as the 1950s—and following close behind “the chicken of tomorrow”—the problem of antibiotic resistance began to emerge. The meat industry has largely ignored the overwhelming evidence that the blanket use of antibiotics has led to widespread antibiotic-resistant pathogens in our food and environment. Until recently, the industry stubbornly resisted any limitations or changes to a system that costs additional hundreds of millions if not billions per year and kills tens of thousands of consumers. As of 2014, over fifty thousand deaths per year were caused by antibiotic-resistant infections in the U.S. and Europe.9

In fact, Consumer Reports has found that the average mass-produced chicken in the U.S. is a pathogenic bacterial bomb waiting to happen, with only one in three chickens tested by Consumer Reports free of pathogenic bacteria.10 For years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has railed over raw (unpasteurized) milk, comparing its consumption to playing “Russian Roulette,” yet chicken is a truly dangerous food that is available in every single supermarket in America. The bacterial odds of industrial chicken consumption make Russian Roulette seem a more enticing option by comparison! In spite of clear evidence of pathogenic risks, the FDA, USDA and other government agencies have been slow to do anything substantial about this threat.

Although antibiotics were the first dangerous and environmentally deleterious growth promoter used in meat production, they were not the last. Until recently, regulators also allowed arsenic as a growth promoter in chicken feed. The FDA downplayed the use of arsenic as a problem, but the decades of arsenic use in chicken production have left large swaths of the nation contaminated, especially in areas where the immense amounts of confined chicken excrement became fertilizer for field crops.

WHY REAL CHICKEN

There is a great deal more to the story of chicken. It is a story worth understanding, because chicken, more so than any other meat in America, encapsulates our national story of food and farming. This includes the change from a decentralized, ecologically oriented system to a consolidated, industrially minded system, as well as the change from consuming natural food stuffs and forages to relying on isolated nutrients and pharmaceuticals to stave off the damaging effects of low-quality food and lifestyles.

If there is any meat for which it is worth paying a premium price, it is poultry. Few foods pose as great a danger to our health (both personal and environmental) as industrial chicken, and few foods depend as much on government subsidization and protection. Finally, few foods offer such a powerful opportunity to change the way the American food system works by voting with our forks and dollars for real farmers.

SIDEBARS

INDUSTRIAL EGGS

Many people once considered eggs a special treat. Historically, hens produced fewer eggs, and many of those were

reserved for hatching to replenish the flock. Eggs also were generally only available seasonally. People were amazed when Laura Ingalls Wilder was able to get her chickens to lay during winter in the 1910s. This feat was so spectacular at the time that it played a crucial part in her writing career.11 Wilder’s success came from basic science: she watched how what she fed her chickens influenced their condition, until she found a balanced diet that provided all the nourishment the birds needed without causing them to gain excess body weight and stop producing eggs.12 Like industrial chicken, mass-produced eggs have become a mainstay of the American diet.13 By 1960, the average American was consuming around two hundred and sixty eggs a year or more, almost an egg a day. Laying hens have had to keep up, and they have, increasing production from less than one hundred eggs per bird per year to almost three hundred in the course of a half century.

ONGOING PROJECTS SHARING THE BENEFITS OF A WAPF DIET FOR GROWING CHILDREN

Johanna Keefe, PhD (C), MS, RN, GAPS/P is completing a doctoral thesis through the California Institute of Integral

Studies’ Transformative Studies program. Her work reveals, with in-depth interviews, the lived experiences of a small sample of women who have chosen, as mothers, to follow a nutrient-dense diet based on the research of Dr. Weston A. Price. While her interviews are now completed and she is in the analysis phase of her writing, Johanna wishes to continue with post-doctoral work by gathering a larger sample of stories, especially from mothers who have watched their children grow over time on a traditional diet. In her effort to reach the widest audience and to inform young women of childbearing age, her future vision may include a published collection of stories and possibly a film, to enlighten the hearts of our future parents and grandparents. To this end, Johanna has conceived of a research blog, Growing Success Stories, to invite just such parents to connect with her vision by sharing their story. If you are such a mother, please consider visiting https://growingsuccessstories.org/. Johanna looks forward to hearing from you through email at jmkeefe@endicott.edu, or by phone at (978) 290-0266. Thank you! Together we will contribute to a return of a flourishing, thriving and resilient new generation!

REFERENCES

1. Kiefner J. Chickens rule in year of the rooster. FarmWeek-Now.com, February 24, 2017.

2. Super T. State of chicken: consumption at all-time high. The National Provisioner, October 24, 2016.

3. McKenna M. Big Chicken: The Incredible Story of How Antibiotics Created Modern Agriculture and Changed the Way the World Eats. Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2017.

4. Gordon JS. The chicken story. American Heritage 1996;47(5). https://www.americanheritage.com/content/chicken-story.

5. Martin P. The 500: how Cecile Steele began a multi-billion dollar industry. http://broadkillblogger.org/2016/12/the-500-how-cecile-steele-began-a-multi-billion-dollar-industry/.

6. NC Soybean Producers Association. History of soybeans. http://ncsoy.org/media-resources/history-of-soybeans/.

7. Clayton C. USDA: ARC-PLC payments coming: USDA announces roughly $8 billion in farm program payments for old-crop year. DTN/The Progressive Farmer, October 3, 2017.

8. Burton N. Sodium use in poultry production scrutinized. Food Safety News, March 2, 1010.

9. McKenna M. The coming cost of superbugs: 10 million deaths per year. Wired, December 15, 2014.

10. Consumer Reports. Dangerous contaminated chicken: 97% of the breasts we tested harbored bacteria that could make you sick. https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2014/02/the-high-cost-of-cheap-chicken/index.htm.

11. South Dakota Historical Society Press. Wilder’s chickens. The Pioneer Girl Project, May 21, 2015. https://pioneergirlproject.org/2015/05/21/wilders-chickens/.

12. Hines SW (Ed.). Laura Ingalls Wilder, Farm Journalist: Writings from the Ozarks. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

13. Carbone J. Chicken, eggs, and the changing American diet. Smithsonian, April 7, 2015.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly magazine of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Winter 2017.

🖨️ Print post

Thank you for the all research you do, and information you share to help us make healthy food choices..