Print post

Print post

The Karen tribe in Thailand. The Daasanach in Ethiopia. The Mount Hagen festival in Papua New Guinea. Mary Ruddick, a nutritionist, researcher, and adventurer, describes what she learned during her field research among indigenous people groups this summer. She goes over what buoys good health and what weakens it, the traditions we would do well to emulate, and the modern conveniences we should eschew. She also describes her “throne of health” framework for optimizing our health, wherever we may live.

For more from Mary, visit her website: EnableYourHealing.com

To order Wise Traditions conference recordings: WiseTraditions.org/recordings

Check out our sponsors: Marithyme Seafood and Optimal Carnivore

—

Listen to the podcast here

Episode Transcript

Within the below transcript the bolded text is Hilda.

What do indigenous people do to maintain optimal health? What lifestyle, community, and dietary habits do they maintain to stay healthy and vibrant? This is Episode 455, and our guest is Mary Ruddick. Mary is the Director of Nutrition at Enable Your Healing but she can most regularly be found endangering herself in the untouched corners of the world to learn from and distill the wisdom of the last remaining traditional cultures. She discusses insights from her trips to Papua New Guinea, Ethiopia, and Thailand. She talks about what she observed there and what she has gleaned from her research of countless cultures and people groups and how it has shaped her framework for health.

Before we get into the conversation, I want to let you know that Mary gave a full-length talk at our October conference in Kansas in 2022. If you would love to hear her and other experts, you can. The talks were recorded, and this kicks off a flash sale of every presentation made at the Wise Traditions Conference. From January 1st through the 7th of 2024, you can purchase all of the recordings as a set or purchase individual talks for 25% to 45% off the regular price. Go to WiseTraditions.org/recordings to take advantage of this deal.

—

For more from Mary, visit her website: Enable Your Healing

To order Wise Traditions conference recordings: WiseTraditions.org/recordings

Check out our sponsors: Marithyme Seafood and Optimal Carnivore

—

Welcome to the show, Mary.

Thank you so much for having me. It’s good to see you.

You are such an amazing inspiration with your experiential anthropological work, fieldwork, and research. I know you personally now. I’m blown away by all that you bring to the world. I’m so thankful that you spoke at the conference. I want to ask you a little bit about your travels. Let’s start with your visit to Papua New Guinea. You went to the Mount Hagen Festival, but there’s more to this story than what happened at that festival. Tell us what you experienced.

Papua New Guinea is such a vast landscape. It was not colonized until years ago. Many parts of it still hadn’t been explored by the outside world until years ago. Much of it, at least from what I had read, seemed to be rather untouched. It was fascinating. One of the places that I went to was Simbai. You take a few different flights once you get to Papua New Guinea and then you get into the village area by a tiny commuter plane that goes once a week, but there’s no road or anything that goes there. The people can’t leave because they don’t use the financial system, and the only way in is by plane.

There is some modernization there but it was fascinating to see how different it was from other places. That’s all in the Mount Hagen area. In the Mount Hagen area, there are so many different cultures. We’re talking about an island of over 700 different tribes and indigenous cultures, and they all have different financial systems, languages, and cultures.

One of the reasons why I wanted to go to the Mount Hagen Festival is because it’s one of the biggest festivals that they have all year. These festivals were brought about to bring a union among the different indigenous groups where they could show off what they’re proud of and not fight. Instead of fighting with each other or fighting over land or other things, they would be coming together and showing their songs, dances, outfits, and everything that they are proud of.

I wanted to go to this because I thought it would be a great way to get into the Papua New Guinea cultures and learn more about a very broad range because as you experienced with me in Ethiopia, when you jump to different ones, a lot of times, I’ll do that when I’m first going to a place so that I can then see, “This one is worth going in for a long stay or this one for a moderate stay. This one is too modern for what I’m looking for.” It helps me to weed out where I want to travel to.

The Mount Hagen Festival was amazing, but what was a nice surprise was that there was a secret one. Maybe I shouldn’t be talking about this, but I imagine not too many people are going to Papua New Guinea. There’s a secret one that’s held before the festival starts. The festival is in a city called Mount Hagen, and around it on the outskirts, you can see buildings and things. This one is held in the forest. There are trees, and there’s nothing in the backdrop. These epic people come marching in with these strides I’ve never seen before in this posture and this presence. You know how many cultures I’ve stayed with, and this was very different. It was different and impressive.

Does each tribal people group come in with their costumes, traditional clothing, stuff, and whatnot? I can imagine what an impressive display that might be.

Some of them are more warring cultures. In those cultures, the men all have these huge weapons that they’re marching with, and they’re all muscle. It’s almost like watching a film. For the first time, I felt like I was in a film. I hadn’t felt that before with any of my other indigenous visits, but watching these men walk across the field, and there would be fire smoke in the back, part of it was the atmosphere of the feathers and the outfits that are used because they pull everything from nature as all groups do.

In Papua New Guinea, there are very exotic birds. There are birds of paradise, and they have these very long feathers. The men put them in these elaborate headgear. The holy men who I’m dying to go back to visit and stay a long time with make hair hats. It’s a very intense process of making a hat out of hair, and it starts when they’re about twelve years old. It’s pointy on the sides. They’re the ones with the yellow face paint. They have these long birds of paradise feathers that come up and move as they move. That feels otherworldly, and that’s why it’s unsettling. This is fascinating, and I would be terrified if I was on the other side of a battlefield.

I’m picturing it. People read this because they want to have a greater understanding of traditional cultures and wisdom, and they also want to apply it to their lives. What did you observe either in the secret festival or the greater Mount Hagen Festival that might be translatable to our culture? How can we live in that more connected-to-nature and regal way?

My greatest lesson came from visiting a very remote village that had not modernized so much. There was no data. There was no Wi-Fi. Usually, the issue I’m talking about is cell phones. They don’t get a lot of visitors. They would like more because, at this point, they have modernized enough to need to be able to travel, and that requires finances. They do have their financial system.

Papua New Guinea is one of the first places I’ve been to that has a pretty elaborate financial system but they use shells for finances and different types of shells for each culture. Many of them are beautiful, and the women wear them around their necks and then also boar tusks. For many of the Mount Hagen groups, it’s the boar tusks. That’s also used as a dowry for weddings.

I took away a couple of things. First, the more remote area that I went to was a bit sad. That was part of why my presentation was the way it was when I spoke at the conference. Here they are very far away from anywhere. They can’t drive, hitchhike, and hike that far through the mountains. The diet had changed so much from people coming in and bringing things like sweet potatoes and foods that weren’t native to them. They were eating a lot of those, and they were more susceptible to disease from that. They had a condition they were calling the black spot disease but it looked horrific. They didn’t have treatment, and no one had tested it. No one knows what it is.

It was a little alarming coming as a visitor as well. It was newer. It wasn’t something that they used to get. This is a newer condition. What it does is it covers their body in black spots. I saw the scars. That’s why I was asking about it because it was very apparent. They said it feels like for a year, your skin is on fire. There’s nothing that they found to help it. It leaves you with all these scars.

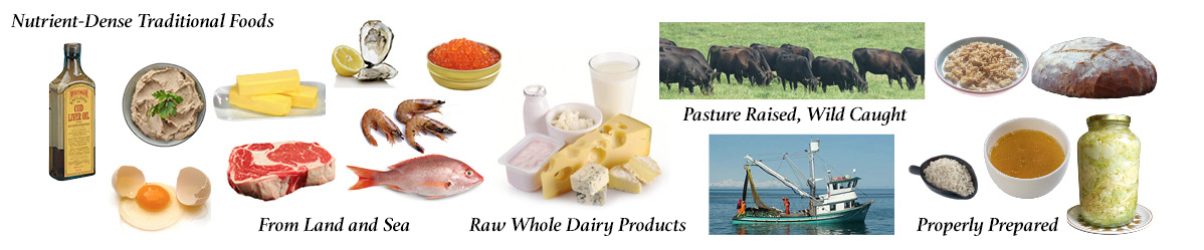

That was very interesting to me but it highlighted that here, they’re living in the same lifestyles. They’re not using lights. They have their feet on the Earth. They were with their families yet they were susceptible to changing some of their foods, not getting as much meat. They’re not allowed to hunt certain animals that they used to hunt. Not having the fats and the proteins specifically, and then the advent of the bring-in of many of the root vegetables that they weren’t eating before offset it. That would be my guess and my theory because I’ve never seen anything like that before, or people being susceptible.

That was one. The other would be when I went to the areas that had stronger health than that but didn’t have those issues. They were impressive. The women were so feminine, and the males were so masculine. It was in a way that I hadn’t experienced before, and I’ve experienced a lot of that in a very beautiful way. Often we have a negative romanticization of the past as if it was horrific for women, and men were jerks. I haven’t found that at all. I found quite the opposite. When cultures are in more traditional roles, the two respect each other because they’re fitting different roles. The male respects the female, and the female respects the male.

So often, we have a negative romanticization of the past, as if it were horrific for women and men were jerks. It’s actually quite the opposite: when cultures are in more traditional roles, men and women respect each other because they’re fitting different roles.

I know many people will think this is silly but this is very well-studied. The way that we relate to each other produces different hormones for us ladies than it does for men. I’m speaking for people who are born females and born males. The hormones that we each need for those systems are different. The ones that cause relaxation, bliss, and bonding for us are different.

Oxytocin is our bonding hormone. Everywhere I went, the women had baby pigs, babies, and all these things that would produce oxytocin for them. For men, the bonding hormone is vasopressin, and vasopressin is produced by doing things for family members and others. They were constantly doing that. They weren’t sitting around at all. You could see how this would work out but it was a quite impressive lesson on masculine versus feminine because it was so apparent in that culture. For anyone who has been to Papua New Guinea or knows it well, in the cities, the gender issues are rife. They’re problematic. I am not speaking about those. I’m speaking about the villages.

I understand. Thank you for explaining that. I want to ask you although you’ve already alluded to it if there were customs among the tribes that you visited in Papua New Guinea that surprised you or would surprise the audience.

One was that up in York Island, there were some very interesting cultures. One that I’ve always wanted to see and visit is the Duk-Duks. You would have seen them. They go to the festivals and things. They weren’t at Mount Hagen but they go to one up North and present there in their full costume, and you can’t tell who it is. No one knows who’s in this group. They’re an utter mystery, and there are other groups like that too.

One that I went to see was the fire dancers. The fire dancers are exquisite. You can only see them at night. They set up a huge bonfire, and then the men come out one at a time often with a snake that they have caught. They’re going to kill the snake that night and eat it but, and there’s a whole symbol behind that and lots of things. The men come out in masks that they have made but the tribe members of the community don’t know who is dancing and who these people are. They’re like spirits. It’s so much of a problem if one of them is made to be known who it is. They don’t allow it. There were a few times when these fire dancers danced in the fire barefoot. It’s an incredible thing to watch.

If we think cold therapy is something, this is amazing. The way they move is incredible too. It puts you almost in a trance but there were a couple of times when the men would fall into the fire. These are massive masks. I don’t even know what size you would equate it to. It’s so big. If the mask could fall at all, there were boys who would run out and make sure that the mask was covering their face as they removed the man from the ceremony.

Anonymity is key.

That’s something I haven’t seen before. I’ve never seen cultures where the ceremonies, the mythology, and the religion are based upon people within the group who stay hidden within the group. I thought that was fascinating. It’s not just for us strangers. It’s for them too. That was a beautiful piece of mystery.

You also went to Ethiopia. You and I had the privilege of traveling there together. I want to ask you what you noticed there about diet and health because you said that in Papua New Guinea, you noticed among some of the tribes that they had changed their diet, and consequently, their health had deteriorated. Did you see the same thing in Ethiopia? What did you notice there?

I saw very different things but that statement would be true. Health was not in perfect condition in Ethiopia. There are a lot of factors going into that. There have been a lot of political factors. When you and I were there, there was quite a big issue with the president giving tribal land away. Many of the indigenous cultures were moving into villages that were housed by more modern people, and that was causing warfare. It’s pretty brutal. Our poor driver’s whole village was murdered.

There’s a lot going on in Ethiopia that’s leading to that. We saw some of the parasite bellies with the Mursi. I saw that for sure. The Hamar looked healthy to me for the most part but you could see the change and also the encroachment of civilization. Although people were barefoot. Living in the traditional houses, and having a lot of the traditional foods, I don’t know about you but I loved going into the houses, holding the children when you sang, and having coffee with the women and the children. I loved all of that. They were far healthier than I would be if I was living under those conditions if I went and moved in, no question.

I didn’t see chronic disease, arthritis, glaucoma, eye issues, and osteopenia or the curvature of the spine. I didn’t see the typical things that you can easily see in an elderly person in our population. I also didn’t see weight issues either. They have beautiful postures, eye contact, and mood. Children were sweet, hilarious, and a little impish but I didn’t see perfect health that I’ve seen in other parts of the world, and I do think that has to do with the conflict. What did you think?

In some tribes, the groups were obeying the government orders to not hunt. That was negatively impacting their health because they weren’t eating their traditional diet anymore. It was mostly the sorghum and porridge out of that with some cabbage. That’s not providing the nutrient-dense diet that these people need or have traditionally thrived on in some of the groups. In others, they surreptitiously, as you may remember, said, “We’re told not to hunt but we still do.” The Daasanach still get crocodiles, other meat, and important nutrients into their diet. I noticed that.

Here’s the other thing that comes to mind. It was the Karo tribe that told us this. When they were telling us, “We feel assailed by malaria, yellow fever, or these different issues,” they were also able to point out the trees or the plants in the area. They’re like, “That’s the one where we get the leaf to make a tea to alleviate that sickness”. They were surrounded and understood the wisdom of the plant medicine that was given to them by God.

That was so nice to see mainly because when I’ve gone to other places that have partly modernized in Uganda, they didn’t know the medicinal plants to use because the illness was so new. That was very refreshing to see that they had plants and tools in nature to use because nature does always have a tool to use. Do we have the eyes to see it? I thought the Dorze were incredible. I could move right in. They were so healthy and happy. I loved their lifestyle. I loved their food and all their arts and crafts. We made fabric together, their beautiful woven works, and their fermentation methods. They’re a little slice of paradise.

To describe their homes, at first, we thought they looked like beehives, and then upon closer examination, we realized they looked like elephants. They’re carefully woven because the Dorze are known for their weaving abilities. Going back to what you were saying about the differences between men and women, in pretty much every village we visited, the roles were very distinct. The women stayed back with the children, prepared the food, and so forth while the men were in the fields, hunting, and providing the food. The roles were very distinct. In the Dorze tribe, the women would prepare the wool, and the men were the weavers. I thought that was fascinating.

I did too because now, that would be so rare to find. The Dorze are more intact in that even though they have modernized in some ways as we saw some phones there, and some of them have cars, their lifestyle is very traditional. Feet on the mud, living in hand-woven houses, the lighting in the houses, and all of it is so traditional. It’s the same with the food, and because they live up in the mountains and because they have no competition for land or water, they have more than enough of everything. They haven’t dealt with some of the political social issues that the other groups in Ethiopia and the Omo Valley have. Their health seems so much better than the others.

They did. Do you remember their singing while they were weaving?

It was lovely. It was very beautiful. They were creative.

—

Coming up, Mary talks about her throne of health paradigm, a framework that she’s developed based on what she’s seen in the indigenous cultures she’s visited around the world. Applying its principles to our lives can help us improve our health and reverse disease in our modern world.

Go to Marithyme Seafood and use the discount code WESTONA for 10% off your first order. Eat wild.

Go to Optimal Carnivore and use the code WESTON10 to save 10% on all of their products, including the grass-fed organ complex that I mentioned.

—

I want to go now to your philosophy on health. You call it the throne of health. You could tell us the four legs of it. This isn’t something you came up with out of the blue but after studying all these cultures over the years, you have a framework that might help us also thrive and live our best and healthiest lives.

Often after all of these travels, people will often ask me, and I know it’s your question at the end too, “What’s your one takeaway? What can we enact?” The reality is that whether I’m talking about reversing a chronic illness or what I experienced in these traditional, semi-modernized, or semi-traditional cultures, it’s varied. It’s so many things. I’ve pondered for a while, and I was thinking about it.

I don’t know about you but many people will say, “It’s the lifestyle.” They’re with their families. They’re outside. They’re all these things. While I’ve seen people heal through lifestyle alone, and it’s far more important than people consider, I do see that in the communities where even 1 or 2 foods are modernized but the lifestyle stays the same, the health starts to weaken. I started to think, “What is it? What am I seeing?” I was able to put it in four categories.

The other thing that I noticed though was that everywhere I go is so regal. All the people are so regal. The posture, the character, and the presence of each individual person are both impressive and warm. It’s the best virtue of character. I thought, “There are four legs to a throne. If you cut one leg off of the chair, it topples. There’s no more throne.”

That’s what we have seen. We have gone from this beautiful regality among the indigenous cultures even though we tend to think of the indigenous as rough because of Hollywood, history, and other things, “They have medical issues. It’s dire.” It’s this beautiful and heartwarming experience and a life that we can only dream of. It would be our utopia.

To see that, they have all four legs. Do you ever see people who look regal? People’s posture isn’t good. Their mood isn’t good. Their character is waning. It’s a struggle. What I thought of was the four legs. One is lifestyle. That’s your light. That’s being on the Earth. That’s your timing of sleep and eating. All those things come into play. One is diet. That’s going to be the traditional pre-colonial diet for each region, which is different in each region.

Another is the community. People don’t like me to say this but it’s true. I have not seen any introverts to this day, and I didn’t think anything of being an introvert before. I don’t think it’s a character flaw. I want to state that but it’s something that I’ve noticed that was so surprising because we don’t think of introversion as anything less than normal. It’s a personality type but it’s not something that I see in these communities. There’s no question that we are communal animals. A lot of our systems suffer when we’re alone. One is the community, and that involves singing and all of the rituals in daily life, including snuggling at night. No one sleeps by themselves.

We are communal animals. A lot of our systems, including our immune system, actually suffer when we’re alone.

The last one is mindset because it is so present. Everyone is present with no worries for the future and no depression about the past. They’re very much right here with you without anxiety or stress. The eye contact and the overall healthy stoicism are beautiful. It’s not a no-empathy stoicism but real stoicism that comes from a heart-centered place. I see those four things in place in healthy communities.

You’ve given me pause because these are things that are so key, the diet, lifestyle, community, and mindset or mindfulness. It is amazing. That is something that we can all look forward to more of in 2024. We can take steps to move in that direction. Can you tell us some of the things that you personally do? You travel the world. How do you make sure the four legs of your throne are steady?

It’s different in 2023 than it has been before but in general, I kept a very tight daily schedule regardless of my time changes. That’s wavered a bit. 2023 was a bit different but before that, it’s always the same lifestyle pattern in the morning wherever I was. I would wake up and do my gratitude journal. That was often a letter to loved ones that I would then mail. That kept me connected even when I was traveling. I pick up friends everywhere I go. I’m never alone.

Those are your souvenirs. I love it so much.

Whether I’m on a plane or anywhere else, I end up with someone else coming along. For many people, that can be rather aggravating but it’s how I am. I pick up the stragglers. I stay pretty tight with my community even with WhatsApp. I have a group of my girlfriends from growing up. I have a lot of my same friends from when I was a child. We stay tight. I stay in touch with my clients as well. I have a lot of programs that I touch base with whenever I’m in Wi-Fi with everyone. It’s my community and my lifestyle.

My diet is the easiest part. People think diet is hard when you’re traveling, and it’s the easiest. 2023 was so different for me for a number of reasons. I ate some foods on the plane but primarily meat or butter. A lot of the places I go to have good food. My history before that was always to fast when I was on a plane no matter how long. I fasted and almost regretted it when I flew to Fiji after Papua New Guinea because there was no food when I got there for the longest time but that is a story for another day.

The food part is so easy because anywhere I go, there’s a traditional diet, and I can always avoid food. Even if I’m served a hamburger, I just eat the meat parts. It’s very easy for me to avoid without having food allergies and make the right choices. I’ll typically travel with some food depending on the flight regulations because we go to a lot of remote places. There are a lot of weight limitations but as long as I can, I’ll bring something like butter, smoked salmon, sardines, some meats, or whatever it is that’s dried.

I have traveled with you. One thing that makes it easy is you are not afraid. Sometimes people are afraid, “Is there going to be seed oil in that?” You do the best you can wherever you go but you’re not cowering. You’re confident because you know the choices you’re going to make are the best for your body.

When I was healing from disability, dysautonomia, Pott, kidney disease, and all that stuff, I didn’t go anywhere if I couldn’t control the food but I didn’t do that out of fear. I did it out of strategy to get better. Once I healed, then I loosened the reins. My rule was always, “Don’t worry about the things you can’t control, and control everything else that you can.” That’s what I still live by. I eat the things I can like meat, butter, or cheese. Technically, like you, I can eat anything now but I still am mindful of my immune system given my history. I like to focus on traditional foods. I’ve lost a taste for the most part of non-traditional but I’m not rigid at all, and I don’t have fear about that.

Don’t worry about the things you can’t control. Control everything else that you can.

Before we wrap up, I want to ask you one more story because I know you went to Thailand, and you got to connect with the long-necked people. Can you tell us a little bit about their culture and what you experienced there?

They’re among the Karen indigenous tribe, which come down from Myanmar and are a bit of refugees in Thailand. I went up to Myanmar as well. There are a ton of different groups in the hills that I went to go and visit. There are so many. We could write a book on it. I loved the Karens. There are four different groups within the Karen. There’s the long-necked and then three others that don’t wear the rings. One wears rings on the ankles and on the calves but not on the neck.

They could be incorrect insights. There were thoughts while I was there because the Karen groups have gotten a lot of criticism for wearing the rings and these things but what many people don’t realize is that they’re in tiger territory, and cats hunt by biting the neck. It’s very likely that these rings are protective and necessary. It became a mark of beauty because these women were not unhappy. They do not feel that they are lesser than, in pain, or tortured. Most of them could take the rings off. Only the very old who had long necks might not but they can take them off and put them back on.

It’s not an issue. Much of what I’ve read about them is not true at all. What I love about the Karen is the non-long-necked Karen are responsible for the elephants. They have this beautiful relationship with the elephants, and they always have as far back as they know in history. Many of the elephant places that you go to that are off the books are run by the Karens. It’s almost like the elephants can pick up the energy of the people who are Karen. They communicate in a different way. I can’t explain it.

My guide was from one of the Karens, and he was from the one that is close to the elephants. When we would meet elephants, they loved him. They would go right up in trumpet and focus right in on him. They had a communion of some sort. I loved the hill tribes. I would love to go back and spend a significant amount of time there and much more time up in Myanmar.

It’s rather difficult to get up there with the civil war going on. You can get up for a day or sneak in but the problem is getting people who will take you because most people who live on the border are afraid of the civil war but there are a number of groups and communities from China, Myanmar, and that whole region that have migrated down to Thailand because there’s no war going on in Thailand.

That’s so fascinating. Thank you for your point about how we may judge or feel uncomfortable about something we see in another culture but we need to remember that it has its purpose. I think about when you and I were with the Mursi. The women there have the tradition of using lip plates to extend their lips. Our interpreter said that the larger the lip, the more attractive the woman is considered. We might think, “How sad that they have to put that in,” but I’m wearing earrings. We have traditions in our Western cultures as well that others might not understand, and we might not even understand where it came from but often, there is a purpose. That is a beautiful story you told.

That’s the difference because many of our beauty items, take all the fillers, all the cosmetic surgeries, and all of these things, aren’t done by repression. Those are done by choice but for beauty’s sake. Typically, what I’ve seen in these traditional cultures is the thing that they do is either for character growth like enduring pain or enduring anything difficult, or it has a very practical meaning behind it. It’s my theory but the rings make a lot of sense.

I think about the Hamar tribe which has the custom of how the women will beat themselves sometimes during the rite of passage where the young men are jumping the bulls. That’s a whole other story for another episode. The women would beat themselves, and we might cringe as Westerners, “Why are they doing that?” yet we get in cold ice baths. We do things to challenge our bodies to build our resilience and things that we see as almost badges of honor. They have their reasons that they do these things.

When you think about it, a lot of these rites of passage, whether they’re for the males or the females, are about finding a life mate. When you’re looking for a life mate, you want someone who can handle hard things and be okay at the end of it. They’re not superficial. They’re very deep and character-driven so that you can show that you’re not a child anymore, and you’re in a position of providership and care of others instead of in the receiving mode, which is different.

Do you think that if our throne of health or those four legs are steady, we will be more empowered to handle hard things ourselves?

I have no question. When I brought in all the lifestyle, the mental work, and the meditation when I was ill even when I was still bedbound in an incredible and undying pain, my life became beautiful when those things were brought in despite the pain. It was a real living nightmare before that. I’ve seen it, and I see it in my clients and other people who are going through these journeys.

When those things are brought in, it’s very different. For those of you who are too sick to go out into the community, the community is not someone who comes to us. We always have to go out. That doesn’t mean physically going out. We could be writing letters, making phone calls, and supporting or helping someone sicker than us. That link to responsibility is important in health outcomes.

I’m so grateful that you are in the pink of health and reminding us about how to cultivate our health. It is mind-blowing to me to consider that years ago, you were struggling with dysautonomia and so forth. Now, I see you, and I’m like, “Most people would want what that woman has.” I’m so grateful that you took the time. I want to ask you as we close. This is a question I often pose at the end here. If the audience could do one thing to improve their health, what would you recommend that they do?

Wake up at the same time every day. Get the sun and get into a place of truly joyful emotion. It’s typically felt through something like gratitude but it has to be a deep emotion. That alone will make every day good.

Thank you so much, my friend. It has been a pleasure.

Thanks so much. It has been a pleasure too.

—

Our guest was Mary Ruddick. Visit her website Enable Your Healing to learn more about Mary and her work to reverse dysautonomia. I am Hilda Labrada Gore, the host and producer of this show for the Weston A. Price Foundation. You can find me at Holistic Hilda. For a review from Ameeanda, “Vital information. I am eternally grateful for this. Hilda and her guests bring life-changing, beneficial information each week, and I learn something new every time I listen. My entire family has benefited tremendously from the knowledge I’ve gained from this.”

“While I sometimes feel like the crazy raw milk lady in my community, I know that I have kindred spirits all over the world thanks to Wise Traditions, Keep up the important work of sharing the wisdom of our ancestors. We need it now more than ever.” Ameeanda, thank you so much for this review. It warms my heart. If you would like to rate us and review us on Apple Podcasts, please do. Give us as many stars as you would like and let the world know our show is worth listening to. Thank you so much, my friend. Stay well and remember to keep your feet on the ground and your face to the sun.

Important Links

- Enable Your Healing

- WiseTraditions.org/recordings

- Marithyme Seafood

- Optimal Carnivore

- Apple Podcasts – Wise Traditions

About Mary Ruddick

Dubbed the “Sherlock Holmes of Health” for her unique ability to expeditiously assess and remediate rare neuromuscular conditions that others have deemed impossible, Mary Ruddick is a seasoned researcher, educator, medical nutritionist, entrepreneur and philanthropist. She can regularly be found endangering herself in the untouched corners of the world to learn from and distill the wisdom from the last remaining traditional cultures.

Dubbed the “Sherlock Holmes of Health” for her unique ability to expeditiously assess and remediate rare neuromuscular conditions that others have deemed impossible, Mary Ruddick is a seasoned researcher, educator, medical nutritionist, entrepreneur and philanthropist. She can regularly be found endangering herself in the untouched corners of the world to learn from and distill the wisdom from the last remaining traditional cultures.

When not immersing herself from the Arctic to the Amazon, she can be found sharing her findings and knowledge via her sought after keynote speeches, 100+ podcast appearances, and her work both in front of and behind the camera. Mary can be found on countless international TV and film productions (watch for the 2023 Netflix documentary, “Food Lies” for her next appearance). Behind the scenes, she leads film crews to otherwise inaccessible tribal regions thanks in large part to her well-established friendships amongst the indigenous. Her writing has been published in the “Wise Traditions” and her own inspirational healing story can be found within Palmer Kippola’s best-selling book, “Beat Autoimmune.”

Print post

Print post

Leave a Reply